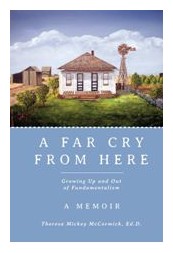

Theresa E. McCormick Celebrates the Release of her Memoir

“A Far Cry from Here – Growing Up and Out of Fundamentalism” details Theresa’s childhood and coming of age as an independent feminist activist

SEATTLE, WA, July 10, 2014, Theresa E. McCormick, Ed.D., Professor Emeritus of Iowa State University, has recently published her memoir, entitled “A Far Cry from Here – Growing Up and Out of Fundamentalism.”

The memoir focuses on stories of Theresa’s whitewashed girlhood, growing up in rural Texas in a fundamentalist Christian family with all their complex relationships, limitations and strengths. These stories take the reader on her journey from a restrictive, limiting upbringing, through the separation from her family and their oppressive religion, and onto the path of discovery of her own spiritual life. This transformation includes her journey into a feminist activist womanhood as a professor, writer and artist.

In spite of Theresa’s flaunting of her family’s core beliefs in fundamentalist Christianity and a woman’s sole role being a dedicated Christian wife and mother, eventually they accept her-the prodigal daughter and sister-back into the fold of the family.

In this transformative memoir, overlapping threads about whiteness, race and gender, and the power of fundamentalist faith to yield security, yet limit growth, weave throughout the stories making this a timely, inspiring, and compelling memoir.

In this transformative memoir, overlapping threads about whiteness, race and gender, and the power of fundamentalist faith to yield security, yet limit growth, weave throughout the stories making this a timely, inspiring, and compelling memoir.

“This book powerfully tells the story of a woman’s struggle to leave behind her religious fundamentalist background and carve out a new identity and life for herself. It tells of her love for her family and her struggle for reconciliation, her commitment to feminism, and brings to life her deep understanding of the people and circumstances of her early years – all combining into an important contribution to women’s studies classes as well as to general readers about a courageous woman’s road to feminism.”

– Riane Eisler, author of “The Chalice and the Blade”

Theresa has chosen to share the following excerpt of her memoir: “Growing up in a Christian fundamentalist home imprinted the fear of darkness, sleep, and death, and it stuck in my psyche and soul over time. The talk I heard at home and at church was all about sin, damnation, and punishment. These terrible words and threats froze my childish vision with fright as solid as a driver’s panic when spinning out of control on black ice. These words and threats retreated into the dark crevices of my unconscious mind to resurface over and over as a vague, free-floating anxiety that I never expressed.”

As a tenured professor, a rare feat among women in academia, Theresa has penned two academic books and numerous refereed journal articles throughout her career, and she has also contributed chapters to several edited books. Theresa served as a professor of education at Iowa State University from 1984 to 2004. She is the author of “Creating the Nonsexist Classroom: A Multicultural Approach.” A talented artist, she has exhibited her artwork at the University of Arizona in Tucson and is currently doing shows in the Seattle area. Looking forward, Theresa hopes to contribute to the ongoing dialogue about what it means to live in a democratic society that embodies social justice, freedom of expression, and equity for people of color, women, homosexuals, people with disabilities, and other marginalized groups. Taking principled action to promote a more equitable and peaceful society in the United States and abroad is her mission.

“A Far Cry from Here – Growing Up and Out of Fundamentalism” is now available for purchase through http://www.ubookstore.com and through http://www.theresaemccormick.com. (See Tab “Memoir Writing.” to read a sample of stories from A Far Cry From Here—Growing Up and Out of Fundamentalism)

My Childhood Home, Oil by B. Christian, Owned by T. McCormick

With 36 Years of Professional Experience,

Dr. McCormick Produced Substantial Body of Work

Active in academia and public education as a teacher, researcher, and writer for 36 years, Dr. McCormick shines as a role model for others aspiring to lives dedicated to being agents of social justice through education and art. She received a Bachelor of Science in Art Education from Oklahoma State University, a M.A. in Art and an Ed.D. in Curriculum and Instruction/Multicultural Education from West Virginia University.

Choosing to be a role model for others during her career, Theresa says, “I simply ‘paid forward’ the gifts I was given by many mentors in my early education.” For example, she became involved in her profession because of inspiration from her high school teacher, Ms. Claudia Neeley who was an artist, an art teacher, and a single woman in the 1950s. Ms. Neeley became Theresa’s first mentor and encouraged her to go into teaching art. Thus, Theresa started her career as an art teacher in the public schools of West Virginia, teaching in summer school programs then, in the Federal Programs: Head Start, Follow-Through and Project Developmental Continuity. During 1977-1979, she also served as multicultural coordinator in those Federal Programs and conducted field interviews with elderly African Americans, compiled and edited their stories into books for classroom use, including ‘The Hollands of Green Street—An Oral History of Elderly Blacks’ (1977-78). (See Tab “Academic Writing” for others in this series on West Virginia Culture and Oral Histories).

During her years in academia (1982-2004), Dr. McCormick taught multicultural, nonsexist education for future and current teachers and also conducted and published research in that area. In 2006, she received the prestigious Willystine Goodsell Award from the Research on Women and Education/American Educational Research Association (AERA). This is an award given to recognize an educator who has served AERA on behalf of women, girls, and education through scholarship, activism, and community building.

A special delight of hers is her years of work with international undergraduates and graduate students. Dr. McCormick was graduate research advisor and committee chair of numerous masters and Ph.D. students from all over the world. Particularly gratifying and mutually beneficial was her work with doctoral students from China, Taiwan, Brazil, and Kenya. Directing the research of these students resulted in further collaborations and international exchanges following their graduation. For example, in 2003, she and her Brazilian Ph.D. student, Claudia Mendes Giesel, attended the World Social Forum in Porto Alegre. Their paper was titled, “Developing Curricula for Social Change and Justice: Perspectives from the United States and Brazil.” In 2002, Dr. McCormick was a Visiting Professor in the Exchange Scholar Program of National Taiwan Normal University in Taipei, and in 1999, she was a Visiting Professor in Kenya at Kenyatta University, where she conducted research and presented seminars and lectures for graduate students and faculty on gender in education. In 1995 she and other colleagues from the US attended the United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing.

After retiring from Iowa State, Dr. McCormick continued working as Affiliated Faculty Consultant with an exchange program to promote curricular transformation between the ISU Women’s Studies Program and the Gender Studies Center at Kharkiv University in Ukraine. In 2005, she traveled with the US delegation in Spring 2005 and gave presentations and workshops on “Women in Higher Education” and “History and Theory of Feminist Pedagogy.” Later, in the Fall 2005, she and another colleague presented a paper, “My Other, Myself: Feminist Strategies for Improving Cultural Understanding When Ukrainian and American Scholars Work Together in Educational Partnership,” at the Comparative International Education Society Conference in Vancouver, B.C.

Dr. McCormick attributes her success to having numerous supportive role models and mentors, in particular, many wonderful women of color, who mentored and helped her to be an effective multicultural educator. Additionally, she’s appreciative of the generosity of her international students and her international faculty colleagues who opened doors of opportunity for global understanding and exchange. The beauty of these relationships is that many of them continue to blossom years after all the projects and conferences are history.

Her books include Creating the Nonsexist Classroom—A Multicultural Approach (1994, Teachers College Press). In 1997, Creating the Nonsexist Classroom received an endorsement as an Exemplary Informational Product from the U.S. Department of Education Gender Equity Expert Panel. (See Book Cover Below). To order copies of the book ($10.00 plus shipping), contact Dr. McCormick at theresamcco@comcast.net

Dr. McCormick also co-authored another book Multicultural Education: Awareness and Activities (2000, Kendall-Hunt), with her colleague, Dr. Lenola Allen-Sommerville.

In 2007, Dr. McCormick published a chapter, “Strong Women Teachers: Their Struggles and Strategies” that appears as Chapter One in an edited book, Gender in the Classroom by David Sadker and Ellen Silber.

In all, she is the author of 28 juried papers or chapters in edited books. (See Tab, “Academic Writing” – Refereed Articles in Journals and Edited Books for a full view of her publications).

Dr. McCormick is available for consulting and presentations on multicultural and gender equity topics at schools, universities, churches, and community service organizations. For example, in 2010, she gave the invited Ernst and Young Lecture for the Women’s Studies Department at SUNY-Oswego in New York on the topic of “Strong Women Peace Activists and Educators.” For more information and scheduling, contact her at: theresamcco@comcast.net.

As An Active Artist, Theresa’s Work Spans Over 50 Years

Starting in the 1960s, Theresa successfully combined parenting with teaching and exhibiting art. Her first one-woman show was the M.A. in Art Thesis Exhibit: “The Art of Stitchery” at West Virginia University. Thereafter, she helped found the Designers’ Craft Guild in Morgantown, West Virginia, exhibiting there and in Pennsylvania. Later, she exhibited in group shows and one-woman shows in Kansas, Iowa, and Arizona. Since 2006, Theresa has had a number of one-woman shows in Seattle. In 2012, she had four paintings in the “Illuminations” show at the Seattle Design Center. Her body of work includes paintings of her travels as well as local and regional scenery. Some of her paintings are abstract, some realistic, some expressionistic, and some whimsical. Included are silkscreen prints (serigraphs), watercolor paintings, mixed media, oil pastels, oil paintings, collages, fabric wall hangings, and pencil drawings. She’s an active member of the Northwest Watercolor Society.

(See Tab “Art Gallery” to view more of her work and go to her facebook page at: www.facebook.com/Theresamcco?ref=tn_tnmn)

For purchases, contact Theresa at: theresamcco@comcast.net

The Past as Prologue*

With an active and productive lifetime spent in education and art, Dr. McCormick finds retirement from academia has opened up new doors for reinvention of herself in exciting ways and for further development of her identity as an artist and writer. Having an extensive background in multicultural and gender studies, she looks forward to continuing to do free-lance consulting and making presentations on topics of white privilege, race, class, and gender as well as doing more painting and exhibiting of her art work. (Contact her at: theresamcco@comcast.net).

Those activities, as well as writing creative nonfiction essays and publishing her memoir, A Far Cry From Here—Growing Up and Out of Fundamentalism, and spending more time with her family, friends and former students around the country and the globe indicate Theresa’s intention to continue creating a life in motion, one day and one story at a time.

(*Prologue—“an event or act that leads to something more important”.)

“MEMOIR WRITING”

SAMPLE 1

Going to Town with Daddy

It’s funny how memory works. Walking down an alley west of my home in West Seattle, I spied a colorful cardboard display box for something, such as candy bars or snack packs. It was quite elaborate with felt at the bottom and several compartments built into the box to show off the products to best advantage. This display box was next to the garbage cans in the alley, ready for the recycling truck to pick up.

Seeing this thrown away display box jogged my memory back in time over 60 years to the time when I went go to town with Daddy to buy groceries and get meat from the walk-in freezer that stored individual farmer’s beef and pork. This was about 1943 when I was four years old. At home, we had no refrigerator or deep freezer to keep our meat. Seeing the colorful display box in the alley reminded me instantly of the thrill I felt when I saw the display cases and boxes for the first time in the grocery store with Daddy. I don’t remember much about the candy or treats in the display boxes; I remember the boxes themselves. I imagined playing with them or perhaps, making them myself: the creativity of the boxes appealed to me. There was something about their unusual construction, design, and colorful logos and pictures on the surfaces that triggered my imagination. I fancied using such boxes for my playhouse. They seemed like small pieces of furniture to me.

Daddy would always buy me one treat of candy or gum from the displays, but that was not my major thrill. I simply loved these trips to town with Daddy for all the sights I got to see. Mama didn’t drive, so he went to town to buy the staples she need for the baking: white flour, corn meal, baking powder, and white and brown sugar. They bought very few canned vegetables or fruits because Mama had a garden and an orchard with peach trees and put these up in Mason jars for storage in the cellar. She raised chickens and turkeys, which were the mainstay meats on our menu; and of course, we had eggs, butter, and milk, from which she made buttermilk and cottage cheese. Daddy also slaughtered a cow and a pig each year and had the meat packaged and put in the walk-in deep freezer in Petersburg where we went to do our shopping.

While I loved going to the grocery store with Daddy, I was a bit frightened and definitely in awe of walking inside the freezer locker. Staying long enough (probably only five minutes at the most) for Daddy to select the cuts that Mama had written on the grocery list, seemed like an eternity to me. Her list usually read: one chuck roast, two pounds of bacon, and one pound of sausage. This walk-in freezer was a separate business from the grocery store, just down the street a few doors.

During these trips to town, Daddy filled up the car with gasoline and shot the breeze with the men working at the Texaco station. Sometimes, he had some business to take care of at the Farmers and Merchants Bank. Farmers had to keep on good terms with the bank’s loan officers. The feed stores in small rural towns in Texas were hubs of activity. Here, Daddy bought seeds for his crops, feed for Mama’s chickens, and other farm supplies. Although the chickens ran free, I remember him buying “mash” for the baby chicks.

I loved seeing the baby chickens for sale in crates at the feed store. The ‘peep-peep’ chatter they made was loud and distinctive, but not shrill. Daddy bought these little ‘peeps’ and Mama fed them until they were big enough to scratch for themselves.

I remember Mama catching a chicken or two in the hen house, wringing their necks, around and around in the air until it died. This was the closest I came to seeing how our farm animals were ‘processed’ in order to become food for our table. I never saw the actual slaughter of a cow or pig. I remember Daddy and my brothers slaughtering and gutting a hog at a distance from the house out by the barn. Mama told me what they were doing. I could see them bending over a long wooden trough working very hard. But I never ran out to see for myself.

After Mama killed the chickens, she hung them up on the clothesline to let the blood drain out. She then had to pluck the feathers, wash the bird and cut it up into frying pieces. She made the best fried chicken in the world, I thought. We’d never heard of nor tasted KFC.

Daddy and I returned from town with the car loaded down with groceries and farm supplies. I was filled with new fodder to feed my imagination that would nourish and fill my hours of solitude playing alone during the week ahead. The excitement of going on a trip, which I still feel about traveling, fed my spirit and imagination as a young child. I began to realize that there were different ways of living than on a farm, interesting people doing unusual jobs. The trips to town with Daddy stimulated my daydreams as I lay on my back in the grass imagining faces of people and animals in the clouds and in my creative play in the back yard.

I wonder about Mama in those years. She stayed home and worked when Daddy and I went to town. Where did she get her creative stimulation? She only went out from the farm home on Sundays and Wednesday nights to church, which in my view, served to reinforce for her that there was no other world “out there,” no other possibilities for her life, than being a dutiful, housekeeper/servant for Daddy and her children.

Mamma and Daddy met when she came to Texas to visit her older sister, Lillie, who was already married. Minnie traveled from southwestern Oklahoma where she grew up with her parents, Isom and Etta Wilcoxson, married Ray Mickey in March 1924, and settled into the life of a farmer’s wife that lasted over 48 years. Daddy fondly remembered their brief courtship, saying to me, “Minnie and me sparked for a few months and then decided to git hitched for life.”

“MEMOIR WRITING”

SAMPLE 2

Needle and Thread

Mama’s hands were always busy, idleness not in her mental vocabulary, nor in the sinews of her hands. When not busy cooking, canning, gardening, cleaning, laundry, or ironing, Mama was crocheting, knitting, tatting, mending, sewing, or quilting. She thought of these needle and thread crafts as practical and necessary to outfit her home and family properly.

I observed her Mama’s fingers at work skillfully knitting and purling and rarely losing a stitch. I wondered how this was done, but Mama never took the time to show me how. All I actually learned to do with needle and thread was through my high school home economics sewing classes, and years ago, Ila, my older sister, had learned little more from Mama about the needle arts than I had.

Quilting seemed to “run in the family” to hear Mama go on about her mother, Grandma Wilcoxson, and Aunt Renee quilting when they lived in Indian Territory up near Hollis. When Mama got married in 1923, she carried on this tradition, often quilting with women from the church. She was proud of the friendship quilt that she and the church ladies made in the winter of 1932-33, during the height of the Great Depression. Each square had a woman’s full name embroidered in the middle. The square, decorated with different creative embroidery stitches and symbols, represented the quilter’s interests. They stitched the squares together, then, the painstaking quilting process began. The tinier the stitches, the better the quilt. Mama prided herself on her ultra-tiny stitches. Hers would put to shame the so-called quilting with quarter inch stitches on the artsy-fartsy quilts shown in craft fairs around the country in the 1980s and 90s.

Mama quilted for the family using up every scrap of cloth left over from sewing new clothes and scraps from old clothes too. Her scrap bags were a dazzle of beautiful colors to my young eyes. That these scraps became beautiful warm covers to snuggle under in the bone-chilling cold when a West Texas “blue norther” hit was truly magical.

When all of the children got married, Mama gave each of us a quilt. Then, she began to make quilts for the grandchildren. Two of her favorite patterns were the Wedding Ring and Grandma’s Flower Garden, but she also made many with Lincoln Log Cabin patterns too.

When I grew up, I knew how to mend, sew clothing, and embroider and also how to appreciate quilting and other fine needle arts. Later, I did my Masters thesis on creative stitchery as an art form and held a one-woman art show of my original fabric and stitchery wall hangings. Yet, a bittersweet feeling always floods over me when thinking about Mama’s handiwork, which was both beautiful and useful. Doing these fiber arts, probably saved Mama’s sanity; however, this activity also distanced her from me. Mama’s fingers were so busy her tongue was stilled in the presence of me, her youngest child.

“MEMOIR WRITING”

SAMPLE 3

Teen Years—Breaking Some Rules

When I was a pre-teen and teenager, I worked in the fields chopping cotton (actually it was chopping the weeds out of the cotton) in the summer and pulling cotton in the fall. But I couldn’t wear pants, jeans or overalls doing this hard work! Wearing a dress really was not more modest given the blowing Texas wind and the constant bending and twisting we did while working. While I resented my parents’ rule about clothing, one thing I am glad Mama required was that I wear a bonnet to cover my face while working in the fields. She made these bonnets too. The headpiece was constructed with plackets that held strips of stiff cardboard she had cut from shirt boxes. These strips kept the bonnet firmly extended beyond the face for protection, while enabling me to see. There was a long fabric flap on each side and back of the bonnet. My bonnet, off-white with a little blue flower design was made of a coarse fabric, which may have been a flour-sack. Flour and feed sacks were used to make useful things like bonnets, aprons, pillowcases, and dish towels.

When I became a teenager, I broke their rule about not wearing makeup by putting on lipstick. In fact, I went overboard with it. I remember licking my lips so that the tip of my tongue would always be bright red. I had forgotten I did that until at a class reunion years recently, someone said–when we were recalling how we looked and acted as teenagers in the 1950s–“Theresa, I remember your tongue was always tipped with red lipstick.” We laughed and laughed at our teenaged tricks trying to be sexy and beautiful.

I always had two pairs of shoes: a pair of nice ones saved only for Church and then a pair for school. Specifically, I remember having saddle oxfords even in elementary school. They were white leather lace ups with a band of black leather across the middle. Appliquéd felt poodle skirts ranked high on our “must have” list of clothes in high school. I have photos of my friends and me wearing saddle oxfords with big circular felt skirts with prancing poodles on the sides. We wore matching short- or long-sleeved pastel colored cashmere sweaters with these full skirts, which came to mid-calf, a very modest length. By the time I was a senior in high school, I had broken the family rule about “no pants.” A photo caught me with boys and girls in Palo Duro Canyon on our end-of-year picnic in 1956. I’m in borrowed jeans and a sleeveless white shirt, wearing my long brown hair in a ponytail and smiling.

“ACADEMIC WRITING”

WEST VIRGINIA CULTURE AND ORAL HISTORIES

McCormick, T. E., Editor. (1977-78). The Hollands of Green Street (An Oral History of Elderly African Americans). Morgantown, West Virginia: Monongalia County Schools/U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare (USDHEW).

McCormick, T.E., Editor. (1977-78). Monongalia Blacks Speak of Yesterday and Today. (Oral Histories). Morgantown, West Virginia: Monongalia County Schools/USDHEW.

McCormick, T.E., Editor and Compiler. (1977-78). Mountain Music: A Book of Shaped Note Music. Morgantown, West Virginia: Monongalia County Schools/USDHEW.

McCormick, T.E., Editor and Designer. (1977-78). Little Mountain Books. (Three Language Experience Readers). Morgantown, West Virginia: Monongalia County Schools/USDHEW.

McCormick, T.E., Editor and Author. (1977-78). Starting Where You Are: Ethnic Crafts, Customs and Recipes. Morgantown, West Virginia: Monongalia County Schools/USDHEW.

TAB “ACADEMIC WRITING”

REFEREED ARTICLES IN JOURNALS AND EDITED BOOKS

McCormick, T.E. (2007). Strong women teachers: Their struggles and strategies for gender equity. Chapter 1 (pp. 1-31) in D. Sadker & E. Silber (eds) Gender in the classroom–Foundations, skills, methods, and strategies across the curriculum. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

McCormick, T.E. (2007). The treatment of gender equity in teacher education. Contributing Author with D. Sadker, et al., to Chapter 7 (pp. 131-149) in S. Klein (ed.). Handbook for achieving gender equity through education. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

McCormick, T.E. (2006). Teaching about religious diversity as a multicultural issue (1991). Article reproduced in Representations of the ongoing struggles for equity and justice in education: Research, theory, and pedagogy in multicultural education. In C.A. Grant & T.K. Chapman (eds.). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

McCormick, T.E. (2006). The F-word revisited—History and theory of feminist pedagogy. Conference Proceedings of the Research on Women and Education 31st Annual Meeting, Dayton, Ohio, October 20-22, 2005.

McCormick, T.E. (2002). Teaching as though both genders count: Guidelines for designing nonsexist, inclusive curriculum. Chapter 10 (pp. 237-259) in H. Roussou & M. Wehmeyer (eds). Double jeopardy: Addressing gender equity in Special Education. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press.

McCormick, T.E. (2000, Fall-Winter). Reflections on becoming a multicultural feminist teacher educator. Women’s Studies Quarterly 28 (3, 4): 69-79.

McCormick, T. E. & Allen-Sommerville, L. (2000). Multicultural education: Awareness and activities. Dubuque, Iowa: Kendall-Hunt.

McCormick, T.E. (1999, Fall). Theresa’s story (pp. 135-137). In Barbara Caldwell. Narrative portraits of women in Iowa–Building appreciation for diversity. Journal of Multicultural and Cross-cultural Research in Art Education 17 (pp. 123-157).

McCormick, T.E., & Allen-Sommerville, L. (1998). Multicultural education: Awareness, strategies, & activities. Madison, Wisconsin: Mendota Press.

McCormick, T.E. (1997). An analysis of five pitfalls of traditional mentoring for people on the margins in higher education. (pp. 187-202). In H.T. Frierson, Jr. (ed.). Diversity in higher education 1. Greenwich, Connecticut: JAI Press.

McCormick, T.E., & McShay, J. (1997). Field experiences bring reality to preservice teachers in multicultural education courses. (pp. 224-232). In C.A. Grant (ed.) National Association of Multicultural Education–1996 Proceedings. San Francisco, California: Caddo Gap.

Rega, B., Rodriguez, L., & McCormick, T. (1997). Where’s the truth? A cross-cultural comparison of Chinese and American newspaper coverage of the Non-governmental Organizations (NGO) Forum on Women 1995 and the United Nations Fourth World Conference on Women (FCWC) Ecquid Novi. 18 (2) 229-246.

McCormick, T.E. (1995). Technology and multicultural nonsexist teaching. (pp. 203-215). In J. Larkin & C. Sleeter (eds.). Developing multicultural teacher education curricula. Albany: State University of New York.

McCormick, T.E. (1995). Reframing the discussion of cooperative teaching and learning in a multicultural nonsexist context. (pp. 199-212). In C.A. Grant (ed.) National Association of Multicultural Education–1993 & 1994 Proceedings. San Francisco, California: Caddo Gap.

McCormick, T.E. (1994). Creating the nonsexist classroom–A multicultural approach. New York, New York: Teachers College Press.

McCormick, T.E. (1992). Mentoring: A support system for multicultural education programs and diverse people (pp. 8-19). In C.A. Grant (ed.) Proceedings of the Second Annual Meeting of the National Association of Multicultural Education—February 13-16, 1992. Morristown, NJ: Silver Burdett Ginn.

McCormick, T.E. (1991). Teaching about religious diversity as a multicultural issue. Religion & Public Education, 18 (1), 117-128.

McCormick, T.E., & McCoy, S. (1990, November). Computer-assisted instruction and multicultural nonsexist education: A caveat for those who select and design software. Computers in the Schools, 7 (4), 105-124.

McCormick, T.E. (1990, Spring). Collaboration works! Preparing teachers for urban realities. Contemporary Education, 61(3), 129-134.

McCormick, T.E. (1990, January). Counselor-teacher interface: Promoting nonsexist education and career development. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 18(1), 2-10.

McCormick, T.E. (1990). The multicultural life of the child. Chapter 9 (pp. 107-129). In C. Sunal (ed.). Early childhood social studies. Columbus: Merrill.

McCormick, T.E., & Titus, P. (1990, Spring). Mentoring: Giving minority women tools for advancement. Mentoring International, 4(2), 31-37.

McCormick, T.E. (1989, July). Excellence and equity in education: Compatible concepts or hostile abstractions? Explorations in Ethnic Studies, 12(2),19-31.

McCormick, T.E. (1986, Fall). Multicultural education and competency testing—conflicts and consequences. Urban Educator, 8(1) 31-42.

McCormick, T.E., & Noriega, T. (1986, Fall). Low versus high expectations–A review of teacher expectation effects on minority students, Journal of Educational Equity and Leadership, 6(3) 224-234.

McCormick, T.E. (1984, Fall). A two-point perspective on art: Multicultural-nonsexist education. Educational Considerations, 11(2) 17-19.

McCormick, T.E. (1984, Spring). Multiculturalism: Some principles and issues. Theory into Practice, 23(2) 93-97.

McCormick, T.E. (1983, Fall). Other people and myself: An heritage arts in education program. National Association of Laboratory Schools Journal, 8(2), 32-40.

See more art on Theresa’s facebook page at www.facebook.com/Theresamcco?ref=tn_tnmn

Site powered by Who’s Who Publishers